This is a story that not many know, about a Russian cosmonaut named Vladimir Komarov. He was one of the first Soviet cosmonauts in the 1960s during the cold war space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. He was the first cosmonaut to fly on more than one space mission, and he sadly became the first human being to die due to space flight.

An Aerospace Engineer and test pilot, he was one of the few exceptional candidates accepted into Air Force Group One, the original Soviet cosmonaut program. He wasn’t medically fit for the program on more than one occasion, but with brilliance in innovation and his talents as an engineer, he continued to be an integral part of the Soviet space program as his comrades made some of the first manned space flights in history.

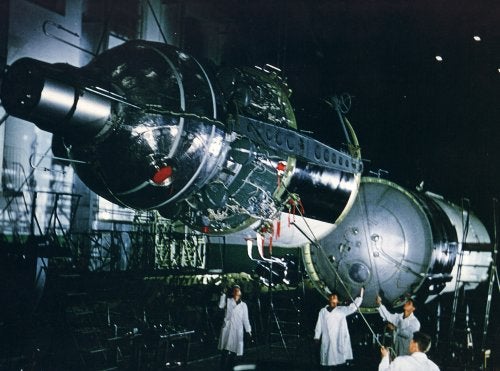

He would finally get an opportunity to venture to the cosmos as the command pilot of Voskhod 1, the seventh manned Soviet space flight, and the first flight to ever carry more than one crewman into Earth orbit. This crew of three men was a big stretch, as some serious concessions were made regarding the safety of the capsule. There was so little space in the cabin that Voskhod 1 had only been designed to hold two cosmonauts, but Soviet politicians were adamant that the craft carried all three.

To fit the three crewmen, the launch escape system and ejector seats had to be removed. This meant that the mission could not be aborted for three minutes, and if there was a failure in the low altitude booster, the entire crew would be lost. Aside from all the safety problems, the three cosmonauts had to go on a strict diet in order to fit into their crew seats. Everything worked out for the best though, as the craft successfully launched on October 12th, 1964, completing 16 Earth orbits over a 24 hour period. The success of the mission had Komarov promoted to Colonel and awarded the Order of Lenin and the title of Hero of the soviet Union.

Shortly thereafter, Komarov was assigned to the Soyuz program along with fellow cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Yuri Gagarin, Komarov’s best friend and the first human in space. Komarov and Gagarin would use their little free time to hunt together, and their families would often spend time together as well. They shared the common experience of facing the dangers of human spaceflight to push the limits of humankind.

.jpg)

During the next three years, Komarov and the others repeatedly clashed with mission engineers over design problems that would compromise safety. Gagarin even sent a letter to Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Communist Party, on behalf of the three cosmonauts, detailing their concerns about the safety of spacecraft designs. They would receive no response.

The beginning of the tragedy of Komarov came with the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Soviet Union, in 1967. Brezhnev decided that a great display of Soviet technological prowess be made, through the rendezvous of two spacecraft. The plan was to have two Soviet space capsules, named Soyuz 1 and 2, dock in orbit, where two crewman would switch places before returning to Earth safely. For this mission, Komarov was chosen as the command pilot of the Soyuz 1 mission, with Gagarin as his backup pilot.

By this time, both Komarov and Gagarin knew that the capsule was not safe for flight, but everyone was terrified of Brezhnev’s reaction if the flight was to be delayed or scrubbed. Their friendship was put to the test as the launch date approached. Komarov knew he would likely die if the mission went ahead as planned. In the book Starman (by Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony), Komarov was told by one of his friends in the KGB that he should refuse to fly. He responded by saying “If I don’t make this flight, they’ll send the backup pilot instead. That’s Yura…. and he’ll die instead of me. We’ve got to take care of him.” before bursting into tears.

As the launch approached, the pessimism of the entire space organization was apparent. Pre-flight tests and inspections by mission technicians uncovered 203 structural problems that would make Soyuz 1 incredibly dangerous to operate in space. On the date of the launch, as Komarov was driven to the launch pad, his dark mood was apparent to all who were present. In order to cheer him up, his fellow cosmonauts started to sing and encouraged him to join in. After a few minutes he began to sing along, and it appeared his mood had somewhat lightened. Gagarin showed up to the launch pad in full gear and tried to convince the crew to let him fly the capsule instead, but he was refused entry by the rest of the crew, Komarov included.

The craft launched on April 23rd, 1967, with Komarov aboard. The problems with the craft began shortly after launch, as one of the two solar panels failed to deploy, crippling the electronics system and some of the navigation equipment. A later attempt to change the spacecraft’s orbit was unsuccessful, and the craft began to spin uncontrollably. The thermal control system malfunctioned, communications became spotty, and the lack of electrical power caused issues with a variety of other systems. With all of these problems, the Soyuz 2 launch was still planned, but was ultimately cancelled due to a thunderstorm. This proved fortunate for the Soyuz 2 crew, since the craft suffered from the same design issues as the first capsule.

With Soyuz 2’s launch cancelled, mission engineers attempted to bring Komarov home at the first available opportunity, but by this point the craft was transmitting unreliable information about its status, and communications with Komarov were completely cut off. The ingenuity of Komarov shone through as he managed to realign the spacecraft and manually fire the retro rockets. On the 19th orbit of the Earth, Soyuz 1 reentered the atmosphere and Komarov attempted to release the main parachute. The drogue was released to slow down the capsule but the main chute did not deploy. The reserve chute deployed but was tangled in the drogue of the main chute, and so the capsule plummeted toward Earth. The cabin exploded upon impact and burned up, leaving little for the Soviet Air Force recovery team to identify.

.jpg)

As Komarov plunged toward his death, US listening posts in Turkey picked up communications of him enraged, cursing those who had put him in a broken spacecraft. Weeks after the crash, in an interview, Yuri Gagarin criticized the Soviet officials who had let his friend fly. The burden of Komarov’s death had put a huge weight on his shoulders, and he became depressed that he could not have convinced Brezhnev to scrap the launch. Gagarin died less than a year later on March 27th, 1968, when the plane he was piloting crashed near the town of Kirzhach. The official cause of the crash remains uncertain.

Komarov was honoured with a state funeral in Moscow. He was posthumously awarded with his second Order of Lenin, and his ashes were included in the Kremlin wall necropolis at Red Square. Before the flight, Komarov had demanded an open casket funeral service, so that his superiors could see first-hand the horror they had caused. An infamous photo (Warning: Graphic image) shows the Soviet superiors viewing his remains, barely recognizable.

.jpg)

Komarov’s sacrifice brought the public’s attention to the dangers faced by the Soviet cosmonauts of the first era. In Leo De Boer’s 2000 documentary The Red Stuff, Alexei Leonov said “He was our friend. Before his death the press and public had paid little attention to the extreme risks we took.”

Komarov’s sacrifice for his friend is a tale of heroism, and an illuminating tale of the dangers of spaceflight during the space race. During the Apollo 11 mission, one of Neil Armstrong’s final tasks while walking on the Moon was to place a small memorial of items on the surface, honoring the Apollo 1 astronauts Virgil Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee, as well as the Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin, and our hero Vladimir Komarov.

Thankyou for the article which fills in some blanks for me.

RIP this fallen hero!

He sacrificed himself, knowing he could die.

This is true bravery.

True hero

Great article. Thank you so much!