Since diving into astrophotography last year, I’ve discovered that I love the concept of time-lapse, and not just with respect to astronomy. It’s amazing to see the changes that can occur over long periods of time, and time-lapse photography is a way to record the changes and see how they unfold. In astronomy the best time-lapses give you a sense of the Earth’s motion through space, show satellites zipping overhead, and show aurora dance along with weather patterns.

Large amounts of time with slow incremental changes produce incredible results when it comes to time lapses. Science communication is about how to show data to the world, how to communicate difficult concepts in accessible ways, and how to see something you would have never seen before. A great example of this is the 365 days of time lapses by Ken Murphy.

It communicates the number of sunny days, cloudy days, day length, season, and lets you compare all 365 days of the year at once. Using this you could estimate the total annual precipitation, and get tons of valuable climate data. It’s like citizen science turned into a work of art. But enough about time lapse.

Astrophotography has another go-to method for producing incredible images, and that is the idea of long exposures. They don’t serve us very well in daily life, because the lights that we use every day, not to mention the Sun, are so bright that any exposure lasting more than a minute will be overexposed, even at low film speeds. But in the world of Astronomy, we are always thirsty for more photons!

In space, photons are a lot more scarce. Most objects in the night sky are barely visible with our eyes, and if we tried to photograph them in the same way we would photograph a person, we wouldn’t get anything useful out of it. But a long exposure time lets that small supply of photons add up, turning an boring image into a world of detail and colour.

Even with a single 30 second exposure, the detail is revealed, and the image is starting to come to life. But as we get to longer exposure times, in this case adding up multiple 30 second images, we end up with more vivid colours, clearly defined features, and details in the dimmer outer regions of the nebula.

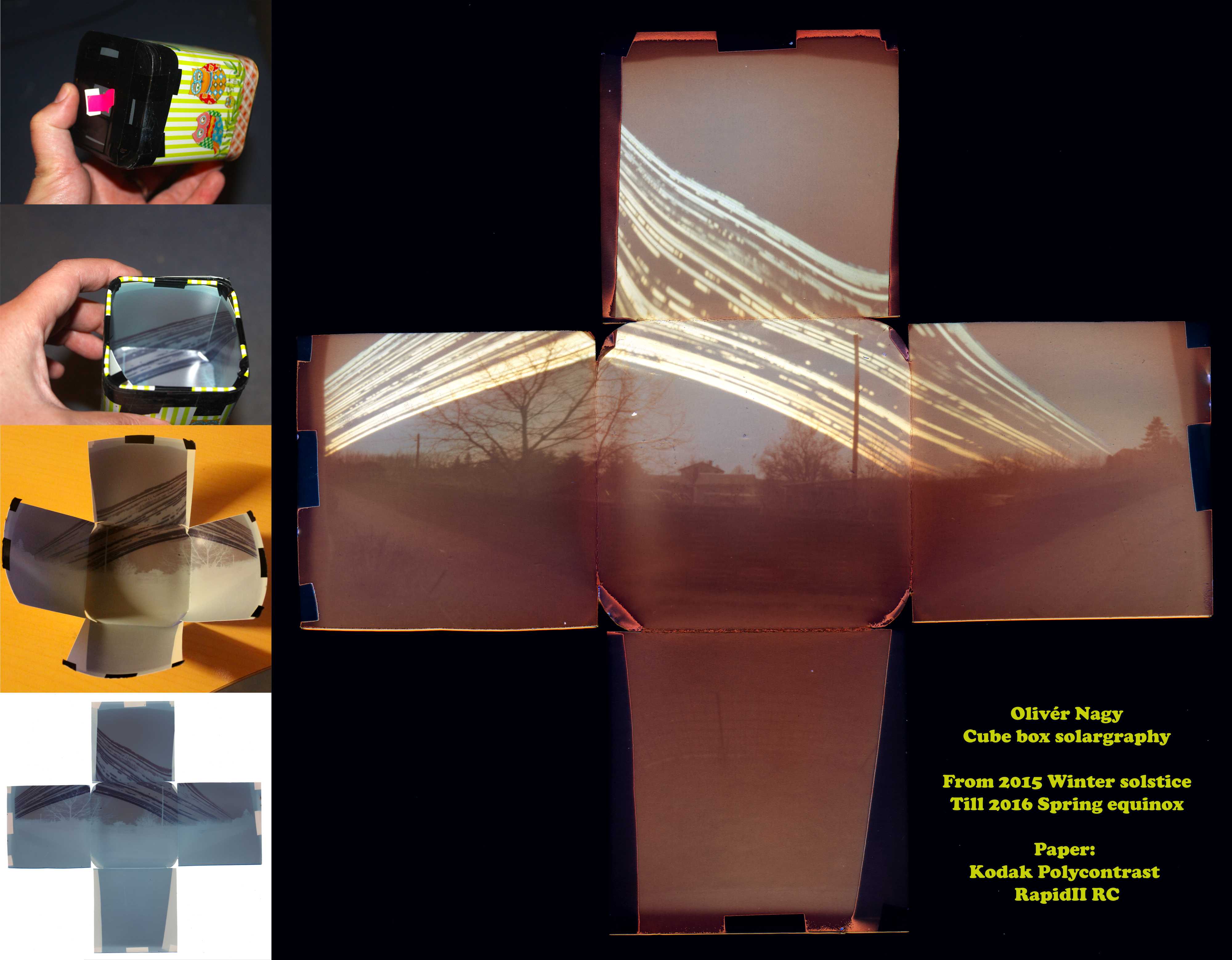

The difference can be quite staggering. But what would you get if you left a camera for three months? Sure the Sun would come up, but that amount of time can reveal something fascinating about the Earth’s motion.

With incredibly slow film and a pinhole to reduce the exposure, you can take images of the Sun’s path through the sky on a daily basis, showing how the motion of the Earth around the Sun changes this path. In three months, we see the path of the Sun changing from it’s lowest path on the Winter Solstice, to halfway to it’s maximum path, seen at the Spring Equinox. the gaps in the path show the cloudy periods during each day. It’s not a difficult project, it just requires a lot of patience.

Astrophotography is a mixture of art and science. It’s about using techniques to bring out the best in what nature has to offer. As I dig deeper into it, I hope to be using my own images as examples. But if it didn’t take time to learn and perfect these skills, it wouldn’t be worth it.