At one point in history, let’s say around 1994, astronomers were fairly confident in their understanding of the formation of planetary systems. Even though at the time we hadn’t found any planets orbiting other stars, they had long been theorized, and we figured that systems would form much like our own solar system. Rocky planets in the interior, gaseous giants further out, and a huge icy debris field at the outer edges.

And then along came 51 Pegasi b. Half the mass of Jupiter, it orbits its star in only 4 days, far closer than Mercury. It was considered a rare anomaly. And then came the rush of what we now call ‘hot Jupiters.’ A plethora of massive gas planets cooking a few steps away from their stars. Clearly our understanding was wrong.

It’s an amazing property of science that the biggest discoveries are not the ones we expect, but the ones we couldn’t have predicted. Today we have a much better idea of how systems form, but it is still a work in progress, with many surprises coming our way each year.

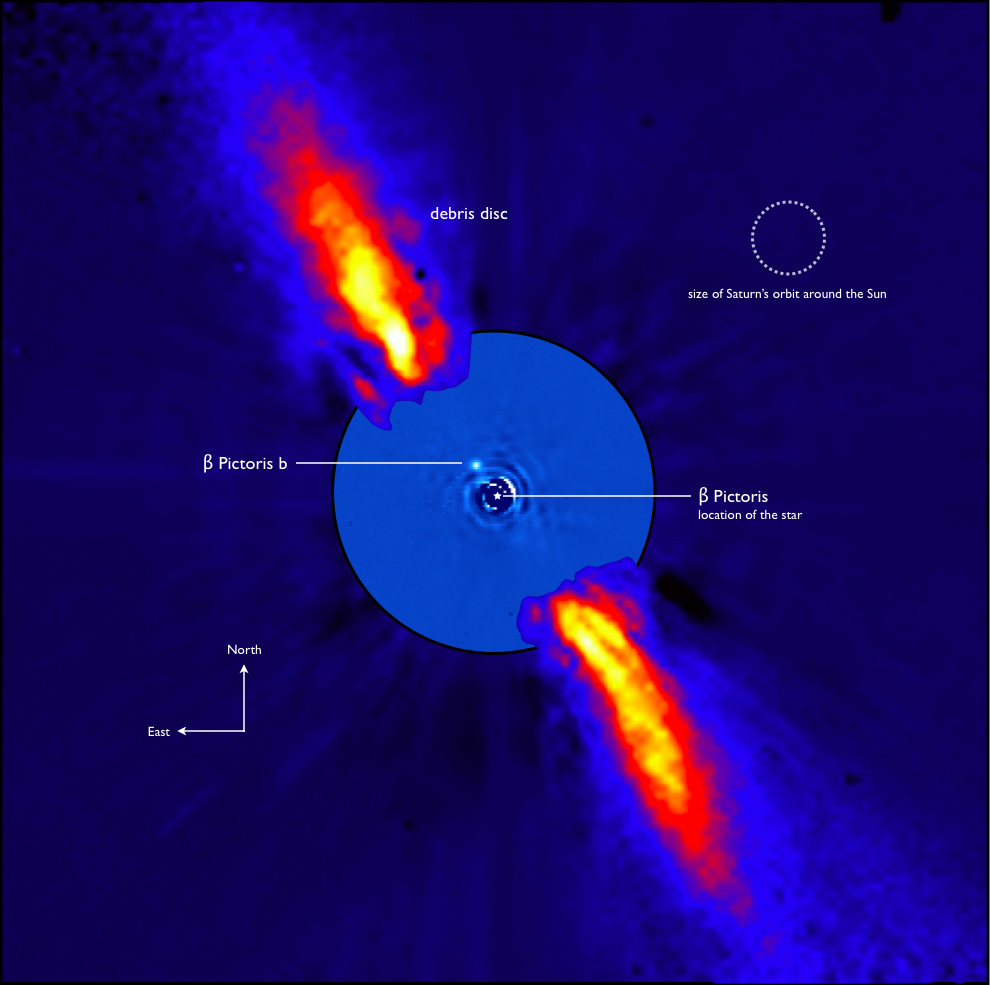

One of the benefits of our technology is that we can start to look at forming planetary systems in real time. The Beta Pictoris system is known to harbour a massive planet about 16 times as large and 3,000 times as massive as the Earth. Located some 63 light years from Earth in the southern hemisphere, the star has an incredibly bright disk of dust and gas, visible due to the scattering of starlight by the dust.

Since Hubble has been in orbit for 20 years, we can use it to recapture old targets to show the evolution of their structure. The companion planet orbits in 18-20 years, and gives us a look at how the young disk of Beta Pictoris is affected by the planet’s orbit. In the 15 years between the images of star, the disk has remained more or less unchanged, even though it rotates around the star at varying speeds. The inner disk, revealed in new images, shows a complicated structure due to the planet’s gravitational pull. It is thought that the disk will eventually form rocky planets or a vast population of icy bodies similar to the Kuiper Belt surrounding our solar system’s eight planets.

The young system, one of 24 young dusty disks imaged by Hubble to date, is considered the best example of what a young planetary system looks like. By looking at systems like Beta Pictoris, we can start to understand the diverse environments in which stars and their planets form. We can start to piece together the much larger puzzle that we started in 1995 when we were surprised by 51 Pegasi b. Still, we have some big steps along the way, and we are certain to say, at least once more:

‘Wow, that’s weird.”